For most of us, our memories of family – the fun times, the sentimental, and the embarrassing -are evocative, and emotional. They take you back to specific moments, of holidays and birthday cake, scoldings and schoolwork, disagreements with siblings, and difficulties overcome.

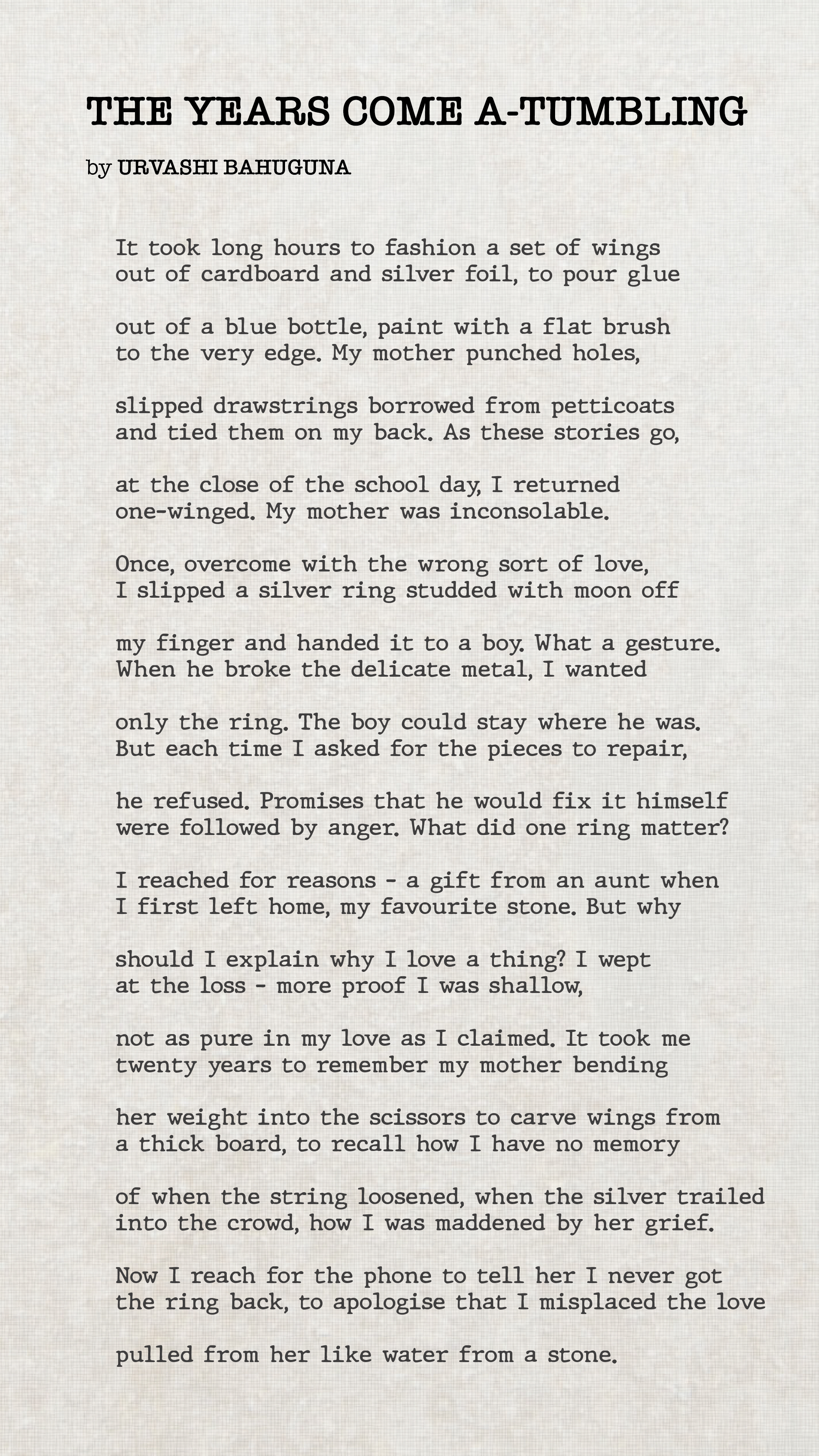

Similarly, Urvashi Bahuguna, in her poem ‘The Years Come A-Tumbling’, revisits moments with her family, but with a different perspective – not good, not bad, just different; it’s the past, in present tense. And by presenting it so, Bahuguna posits that memories are simply prompts for stories we tell, and that the stories themselves are malleable because so is the teller.

We talked to Urvashi about her family, poetry, and the permeance of memory.

1) How would you explain to someone who knows nothing about Indian families, how unusual, and special the dynamics are?

Because Indian families are impossibly varied, I can only describe my own. I live with my parents and my sibling as do most of my friends who work in the same areas as their families.

There’s a continual negotiation of shared and personal space, of responsibilities, of what should be optional and what shouldn’t – sometimes it’s overwhelming, sometimes it’s a crucial support

system.

Similarly, my life is also quite entwined with the lives of my extended family. There’s a lot of dropping in, sometimes with a brief call to check if we are home, sometimes not. It isn’t easy, but we don’t not do things because they’re hard. That isn’t a boast: there isn’t intrinsic value in needlessly suffering.

This is more about personally being in the position of being able to make the most of things and making the choice to do so. My cousin will make the effort to go along with me on a work assignment with me when I’m not comfortable going along. I will take my aunt to buy orthopaedic shoes. Other times, we’ll excuse ourselves to prioritise our own lives.

2) Tell us a little about your family, and how they’ve affected your writing.

While I was growing up, I read from my parents’ bookshelf – Agatha Christie, Georgette Heyer, Romila Thapar, Nehru, Roddy Doyle were some of the authors I ended up reading or at least trying out alongside books from the school library. What they were interested in was what I had access to. With my mother, it was interiors, textiles, art, historical fiction. With my father, it was history, thrillers, astrophysics. Over time, I read what my sister was into as well – Percy Jackson, John Green.

In some ways, my writing is a sum of all our interests.

I still hold that kind of diversification in my reading collections of poetry alongside thrillers. It’s been useful for me to keep changing tracks in my brain, it allows me to think about possibilities (both in writing and in life) in a broader way.

3) Tell us a little about what was running through your mind when you put pen to paper for this poem.

The poem looks back upon two incidents – one from twenty years ago, and one from four or five years ago. I was thinking about how perception is an outcome of what I am able or prepared to see at a particular moment, and I was thinking about the passage of time as a tool to better or further understand the past.

I have a friend who often reminds me that when humans construct stories retrospectively, they tailor it to suit their needs. There’s a convenient story I’m trying to re-write, re-imagine in this poem.

I asked myself what the possible and inconvenient truth was.

Another thing I had in mind was that eventually I might want to write about the second incident (the one with the ring) again sometime in the future, and perhaps then I’ll see that person in a

completely different way. I don’t want to suggest that that process is therapeutic however – it’s more to shift gears in my head, because I am finally ready to do so.

4) Some of the moments/images you capture are so crystalline, such as the imagery of your mother making the wings. How do you locate these moments to help shape the poem?

Location, as you rightly put it, of moments and details for poems is usually a drawn-out process. Sometimes, it’s from notes, other times, while I’m writing a poem, details and associative

memories will organically occur to me, and I will test them out. There’s a lot of trial and error, constant addition and removal, and experimentation.

5) Does poetry offer you something that prose cannot in expressing yourself about your family?

Brevity has been poetry’s biggest gift to me. I hadn’t written about my family before – I needed poetry to get started, I think. Poetry collections have a particular architecture, a way of ushering people from one room to another.

I didn’t want to linger on any particular familial narrative.

I wanted the emotions and perceptions to keep morphing – because that’s the pattern they follow in real life. I was able to stay small and ephemeral in poetry.

6) Is there anything you want contemporary readers to contemplate or question about the way we negotiate our relationships with our families through your piece?

‘The Years Come A-Tumbling’ is one of my favourite poems to read out loud to audiences – it’s the one poem that I’ve probably most heard back from readers and listeners about. What readers glean from the piece, I expect, is filtered through their personal experiences of family, memory, re-calibrating one’s understanding of a person in the light of new realisations.

I don’t want to mould how they interpret the piece, but I can suggest, if someone is interested, two other poems

that look back on past memories with fresh perspective: Robert Hayden’s Those Winter Sundays and Ada Limon’s The Raincoat. These poems are interesting ground to think about what new,

hard-won perspective can bring to old memories.

7) Where do you see your writing heading next? What are you at work on?

I have, other the last few months, been writing a collection of personal essays on mental health. Each essay leads me into new territories, and I can’t see beyond that at the moment. Because there are so many emotional and intellectual turns between now and the completion of that manuscript – I don’t know where my mind will be at when I finish, what new possibilities might or might not have emerged. I am looking forward to watching that outcome develop.

Find more of Urvashi’s work here.