Nowhere is the popular saying ‘You are what you eat’ as straightforward and complicated at the same time as in India, where we symbolically consume identity through our food and drink choices; where whether or not you eat onions, garlic, and beef denotes region, class and caste.

For Dalits, this has historically meant being unable to eat with upper castes or going hungry or thirsty because they were refused food or not allowed to fetch water from the same source as the upper castes. And although social and political change has brought in some change, prejudice is still enacted through food, plus the silence around the cuisine culture of the marginalised continues. Just think about the last time you saw Dalit food on a menu card.

Visual artist Rajyashri Goody explores this interrelationship offood politics at her recent Clark House Initiative exhibition titled ‘Eat With Great Delight.’ Goody, herself of Dalit heritage, displayed a collection of photographs of her family celebrating with food, as well as a booklet of extracts and poems from Dalit literature which she turned into recipes. It is both an attempt to make visible positive imagery of the Dalit community, as well as calling attention to their everyday struggle and resistance under the caste system.

In this interview, she tells us a little more about the exhibition, her relationship with food and literature and how it helped her strengthen the voice of the Dalit community:

1) What do you think is the social power of food? How would you say it impacts the notions of identity and belonging?

I think food is an integral part of everyone’s life – which is why it’s so interesting if we look at the specifics of food such as eating habits or access to food.

I am not necessarily interested in the food itself but how people interact with it and how it discloses a lot of their social position.

2) What inspired you to create your Clark House exhibition?

The Clark House exhibition was mainly family photographs of people eating food during celebrations. These celebrations always included food whether it was a wedding or a birthday.

As much as I did want to talk about Dalit food politics in a sort of critical and complex way, I was more interested in showing positive images of Dalit people and families which doesn’t really exist in the public sphere. Whatever documentation there is of Dalits is mostly hard hitting, and features violent, negative imagery which is not necessarily untrue but there because of the lack of the positive.

Tell us about the recipes you make from Dalit literature and texts, as a recipe, in itself a personal thing, can be an extension of the political.

I became interested in this a few years ago when I found out there was no real Dalit cookbook. I started researching whether there was a Dalit cuisine or if that was even possible because there are millions of Dalit communities all across India. At the same time, with new things coming up about Dalit communities and minorities being targeted for their food practice, I started thinking about whether there is a specific reason why there isn’t a cook book for Dalits.

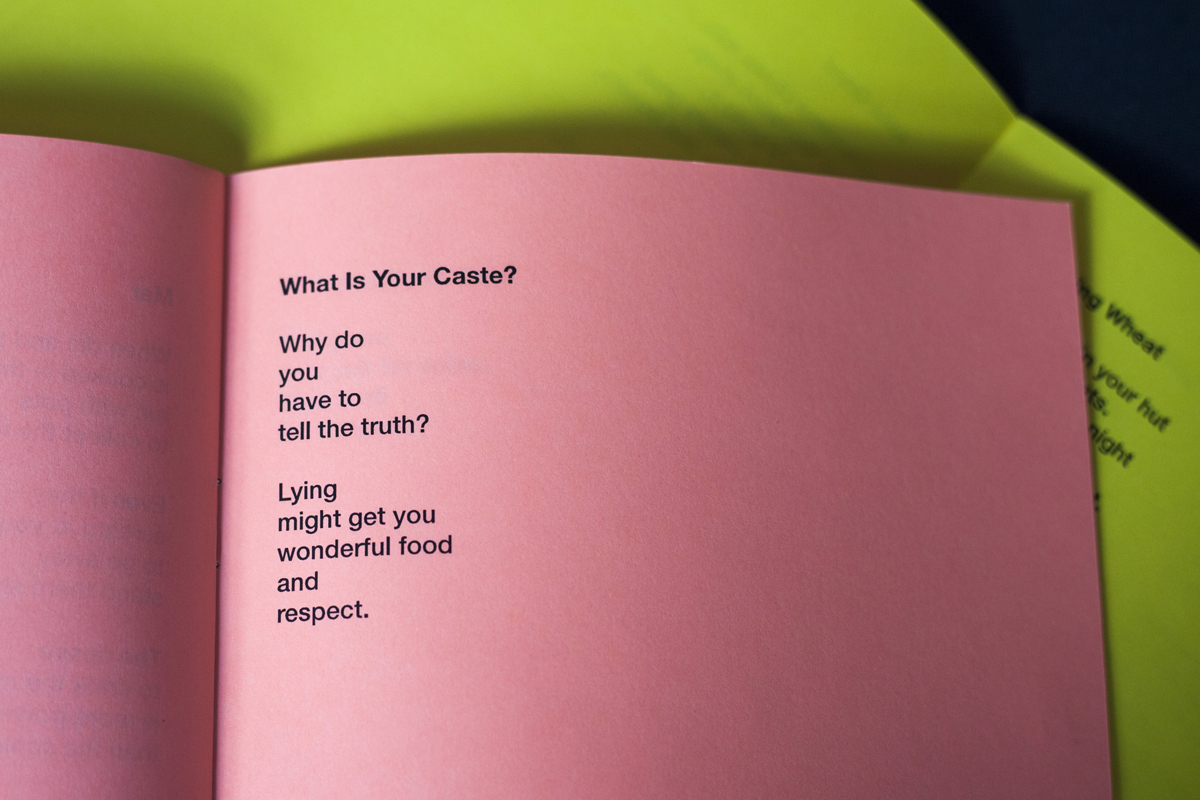

A cookbook is a very simple form of language and literature. It’s not meant to be academic; it’s just supposed to be passed from family to family. It is seen as a very meagre way of writing and reading. Dalit people still don’t have access to education so therefore even simple things like writing a cookbook is out of their league. It became a concept of our people not being able to write our own history – whether that’s in a form of a cookbook or something bigger like an autobiography.

At the same time, Dalit food is very complicated – you may be able to enjoy a certain type of food, but upper caste people would still think it’s ‘impure’. There is still a ‘shame’ related to eating food. There is hunger, not having enough access to food, and no inter-caste dining allowed. In many villages, Dalit people cannot use the same wells other castes can use, they can’t own enough land which makes them depend on agricultural farmers and labourers. Basically, it means they are dependent on what their masters give them as food.

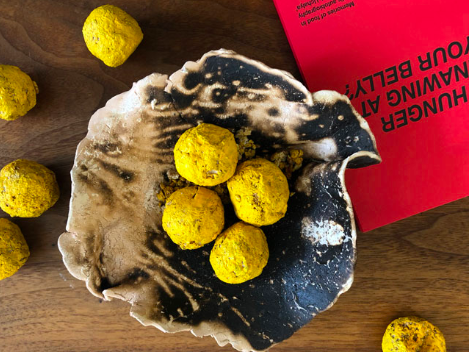

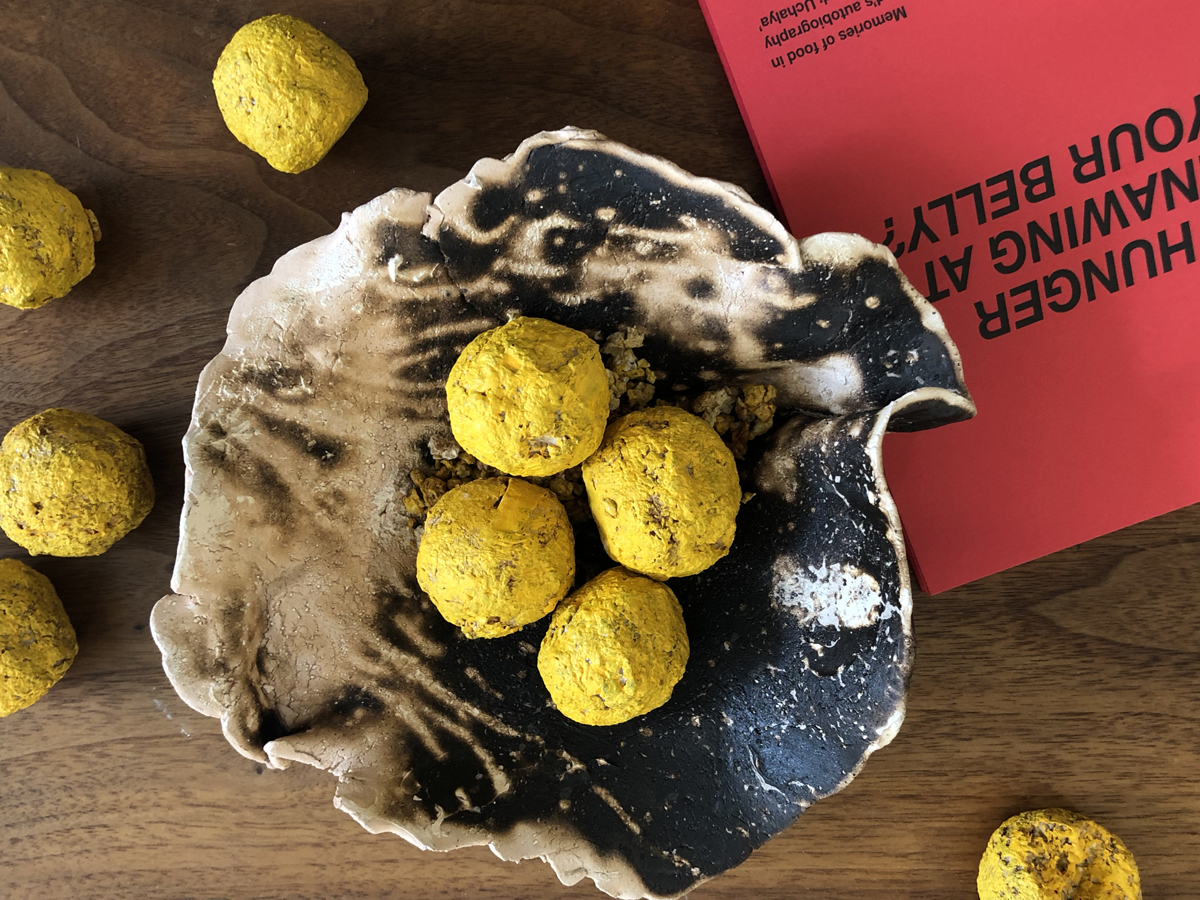

Trying to put this all together, I have made small cookbooks of recipes you can’t really follow, to try to problematise the whole idea of a recipe being universal as in the end it’s really not; everybody’s experience of food is going to be separate and different and often coloured by the social structure you’re in.

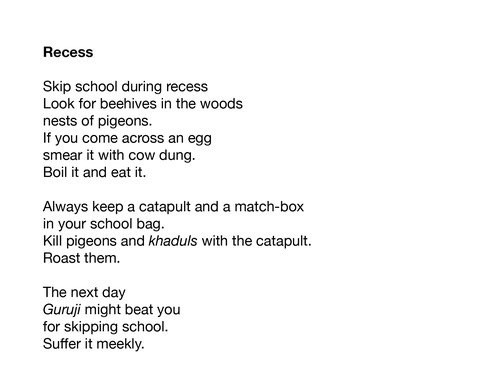

To talk about food from a particular caste position, I would read a Dalit autobiography and would mark out certain sections from it that discusses food. In those passages, the writer may have talked about skipping school one day out of hunger and going to the forest carrying a catapult and matchbox, in order to kill a bird or get an egg, make a fire and eat it. This was at the risk of being punished the next day for skipping school, but the writer couldn’t help it because he was so hungry. I tried to make it very dark and ironic as it shows people how specific people’s foods can be.

3) One of the themes of the exhibition is the relationship of the institution of the family with food. Can you tell us a little bit more about this?

In the end, there is a general underlying sense of sameness within all families when it comes to the way we eat with our family.

My family – even though my mother is Dalit – has been very privileged to get good jobs. I wouldn’t say that my experience being Dalit is like everyone else’s. It’s sort of an insider-outsider experience.

I have never had to experience hunger, but I know mother and my mother’s side of the family has. At the same time, they have been working hard all their lives to ensure that their children didn’t have to go through their experience. Even though our relationship with food now is seen as middle class, there is an underlying sense that it was not possible a decade ago and more.

Those histories need to be remembered. We do not need to feel bad about it; it’s just important to reflect on the fact that some people had to work harder to have a simple meal with their family every day and enjoy it.

Click here to read more about the exhibition at the Clark House Initiative and click here to follow Goody on Instagram.

Interview by Ashavari Baral

All images credit: Rajyashri Goody