“I use my art as a tool to challenge my own perceptions of what my identity as a South Asian and as an American can look like, and I hope to encourage those that share my South Asian American identity to do the same for themselves.”

Asian-Americans have always wrestled with their bicultural identity. Stuck between the East and the West, they either assimilate with one culture, completely disowning the other, or they perpetually keep swinging between the two cultures. Senna Ahmad, a Pakistani-American artist has discovered a third option – an identity that refuses to be limited to the East-West binary. What started as part of a daily exercise to keep herself occupied during an emotionally straining period in her life eventually turned into a project which marries poetic Urdu language with Western melodies. The Urdu Vinyl Project takes inspiration from Mid-Century modern South Asian book design to reimagine album art for English alternative/indie bands.

We spoke to Senna about her project and how she discovered her unique identity through her art. Here is what she had to say.

1. What was the inspiration behind using vinyl records for your artwork?

So much of our music is consumed digitally now, there really isn’t a tangible aspect to what we listen to, nothing that we can touch and feel, that is the extension of the work of the musician. Vinyl records, especially used vinyls, provide that for me.

There is a sort of ritual attached to listening to vinyls and the process almost forces you to pay closer attention and care to the music.

Because this project was the outcome of a deeply personal reflection of a past self, there’s a nostalgia attached to the media that I consumed.

2. How do you think the Western melodies and the South Asian aesthetic blend in? What kind of impact does this concept create on the outsider?

I think there’s this notion that all the things I combined in my project don’t blend with each other and I wanted to show that they can, if you want them to. There’s so much of myself put into this project, and if there’s one thing I wish people would get from my piece, it’s that each of us is so multifaceted in our identities and this should be celebrated.

3. How would you go about explaining the subculture that the hyphen in ‘Pakistani-American’ gives birth to?

I think this looks different depending on where one lives but generally what I see is this set of standards to be accepted as not too “Americanized” but not too “fobby”… terms I hear thrown around a lot. The Pakistani-American people that I was surrounded by were the ones whose values and attitudes towards both cultures I didn’t understand. There was a flat out rejection of anyone who had a South Asian accent. Culture and religion would get confused with one another. To many, Islam and Pakistan were synonymous with each other so there was even a rejection of Pakistanis who did not practice religion the same way you did.

Whatever it looks like, the hyphen for me represents the imaginary line that makes “Pakistani” and “American” binary oppositions which that limit our possibilities, creativity and impact. Rather than interrupting the cycle of stereotypes, we’re just creating our own.

4. In an article, you have written that you “decided to completely let go of the hyphen.” What exactly do you mean when you say that?

I started to think about what my identity looks like without the worry of constantly trying to balance this line of “Pakistaniness” and “Americanness” which for me meant giving myself permission to explore aspects of my identity that I didn’t see in the subculture I mentioned. Music, both Pakistani and American became a big part of this. The albums covers I made for my vinyl project were ones that I associate with the time I was learning to let go. It sounds like such a pretentious hipster thing to say now, but I only know a handful of people that looked like me that listened to the same things I did and it empowered me to embrace exploring culture on my own.

Learning more about Urdu became an important part of letting go too. I grew up speaking Urdu more fluently than my peers and my parents love for Urdu shayari was passed on to me at an early age. This was a time in my life where I had the privilege to explore what the Urdu language meant for me, and create with it in my own unique way. I’m lucky to be living in a generation and a situation where I don’t need to hide my mother tongue as a means for survival, and I want to embrace that as much as I possibly could.

5. What message do you have for other artists who are trying to build a better world using art as their medium?

First and foremost, my advice would be to recognize the narrative that others have assigned to you, and then be brave enough to look beyond it. Search for what feels right to you and embrace it.

Using art to create social impact cannot happen until we are able to notice the patterns that are holding us back. If we don’t recognize these patterns we’ll be perpetuating the same stereotypes we were given instead of building a better world.

Secondly, know who you speak for and who you do not speak for. There’s so much room in this world for all of us to grow and be successful. It’s extremely important to recognize whether we are using our creativity to amplify unheard voices or inhibiting them to amplify our own. This is much easier said than done. Recognizing privileges that serve us positively at the expense of others is a difficult and self confrontational process, but using our privilege to serve others is the only way to move toward a compassionate world.

Apart from being a gifted artist, Senna is also a phenomenal photographer. To check out more of Senna’s work, follow her on Instagram and Flickr.

Written by Rukmini Ravishankar

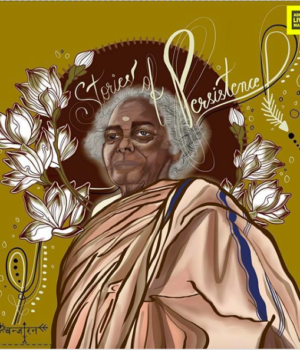

Featured image credit: Senna Ahmad