Anyone who has ever owned a stuffed animal knows its emotional or sentimental worth.

And indeed, whether a toy, piece of jewellery, sepia-toned photographs or faded silk sari, there are objects that we keep close and hold on to because of what they represent to us; laden with years of history and memories, they link us and anchor us to people, places and times. And it’s precisely because of the stories that we can tell through objects, that Aanchal Malhotra and Navdha Malhotra got together to start a digital repository in September of 2017.

Titled ‘The Museum of Material Memory’, their website records India’s material culture, and traces family histories and social ethnography through collectibles and objects of antiquity dating back to the 1970s or earlier. Each object is tied around a story creating a narrative for the time period it belongs to.

Creating A Digital Archive

The idea for the Museum was born from Aanchal’s personal research on objects that were taken across the border during the Partition of India in 1947. While she was compiling information for her book, ‘Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition Through Material Memory’, Aanchal was contacted by several people who wanted to know whether she would be willing to visit them to see their objects. But, most times, it was not possible for her to do so.

“And that’s how the Museum was born!”, she says. “We decided on a digital archive of objects before the Partition up until the 1970s.” This decision allowed the two founders to include more items in their archive, and to expand the periphery of knowledge that these personal artefacts provide.

“Every one should be empowered keepers of our own histories, whether they were oral or material based, and we hope that this contribution format will encourage people to explore their histories further,” they point out.

Empowering Individual History Makers

The website has seven different categories for its findings: Art & Decor, Books, Documents and Maps, Heirlooms & Collectibles, Household Items, Jewellery and Photo Archives. A separate section allows you to submit your own object’s details by answering a few questions regarding its history and current location, along with a few photographs. Aanchal and Navdha urge their contributors to describe the object in great detail and share whatever memory they may have of it. They then convert the responses into a story before adding it to the museum’s collection.

Through the Museum of Material Memory, Aanchal and Navdha hope to create a cohesive archive of material history from the subcontinent. “There has been so much movement in the sub-continent and this is one of the aspects we want to highlight- that we all have a shared history and objects and artefacts simply make that more explicit.”

“Each exhibit not only unravels something unique about a particular person’s history, but also allows us to look at the habits and traditions we share as people of the subcontinent.

A story of one family can speak to the stories of many, just like personal history can at times speak to a collective history.”

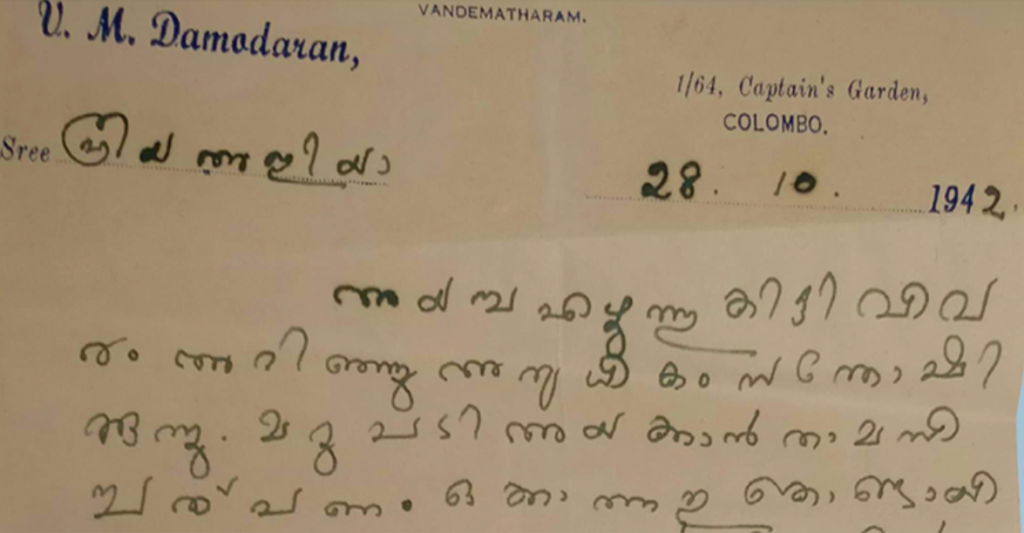

Stories like letters from Ceylon in 1942 written by a migrant worker to his family in India highlights the hardships under British rule and narrates the story of the grandfather who is now remembered as a hardworking and forward thinking member of the family are stories that evoke an image of the society, lifestyle and culture of those times.

Others, like Niharika Joshi’s story about a teacup and saucer set belonging to her grandmother’s sister-in-law is a simple but powerful testament to the bonds that family heirlooms create.

“Our hope is that decades later, people can look back into the Museum and say, ‘these were the things people of the subcontinent used in this time, or these are the clothes they wore, these were the kitchen utensils and metals they preferred, these were the vocations they were a part of and these were the traditions they celebrated,” state Aanchal and Navdha.

It’s very easy to be charmed by the many stories in the Museum of Material Memory, and even easier to be reminded of a memory-laden object that’s precious to you. And if you do have a special story to share, click here to submit your story to the website, and learn when new stories are published by following the initiative on Facebook.

Written by Additi Seth

All images credit: Museum of Material Memory

The letters from Ceylon is written in Malayalam, so I doubt it was written by a migrant Tamil worker. Please do check the facts.

Oh no! That’s an error. Thanks for pointing that out, Fathima. It has been corrected.

There were Malayalam and Tamil workers ,indentured inCeylon.The citizenship woes of these people,was sorted only in the around the year 2000 or so ,if I am right.

This letter will not be a lablourer’s because it is on a letter head and with knowledgeable ‘vandemataram’.

Hi Seetha, you can read the entire story here: http://www.museumofmaterialmemory.com/news-ceylon-1942/