What does your hairstyle or facial hair say about you? Whether wavy, short, buzzcut, shaved or pompadour, the decisions we make about the way our hair is shaped and styled conveys meaning about our identities, the communities we belong to, and the prescribed social mores to which we conform.

When Pallavi Singh learnt that the grooming habits for men in India was still a taboo topic, she decided to investigate. As part of a two-month international art residency programme at the Kochi Biennale Foundation, Pallavi started the ‘Mudivettu Museum – Nirmanathil’, which means ‘Museum of Haircuts – Under Construction’ to investigate the links between identity and masculinity. To get more insight about the grooming habits in Kochi, she reached out to barbers in the city, and in the process, learnt about their struggles and stories as well.

In this interview, she tells us about learning a glossary of hairstyles, the doing away of the traditional image of the macho man in India, and stories from barbers she interviewed:

1) What prompted you to start working on this project?

For the past 5 years, I have been working on the idea of grooming culture amongst Indian men in Indian society. With the passage of time, the concept of grooming has changed, and the area which was highly dominated by women has undergone a huge shift and slowly become shared/taken by men.

When I reached Kochi, I saw the multiculturalism in the city, the exchange of ideas between many communities living together – especially in the field of fashion – and so knew that this was an opportunity to explore my idea further. So, with this in mind, I started visiting local areas in Kochi like Mattancherry, Jew Town and Kochangadi and found that popular culture was influencing grooming habits.

I decided to turn to the barber community for more insight as they were positioned to observe the change in trends.

And when speaking with them, I realised that the professional barber community is pushed to the margin of the society; they aren’t recognised for their work.

Therefore, I thought this project “The Haircut Museum – under construction” needed to tell the story and narrative of a marginalized section of the society that offers a skilled profession, as well as question our contemporary notion of what a museum is, and what it represents. Typically, a museum brings to mind the stories of the elite in society such as kings, nobles and warriors. By placing the professional trade of barbering at the center of the museum, the project seeks to offer new insight and perspective not only about the whole grooming culture but the subaltern side of museum.

I did not remove the term “Under Construction” from my final display as I believe it’s not the end of a story, but only the beginning. This has many layers yet to be unveiled.

2) How have hairstyle trends for men changed over time?

Well, initially, men used to get their hair cut short – not because of fashion, but because of sanitation! And most did not know much about the names of hairstyles or were observant about what trends were making the rounds, so they used to just get a haircut to maintain a neat look.

Changes were brought in when men started to emulate the hairstyles of their idols who would appear in fashion magazines or commercial advertisements for hair products.

This was when styles such as the Mohawk, Pompadour were added to the glossary of hairstyles by barbers and customers.

3) Can we make inferences from these changes? For instance, about masculinity and society over the years? How do unisex salons play into this?

Sure. When men started to pay more attention to haircuts and grooming in general, they did away with notions of what is considered handsome and what is considered ‘masculine’. First, they were engaging in what was usually regarded a ‘feminine concern’, and secondly, they were changing the traditional masculine image of what a man should look like.

I believed unisex salons have played an important role in forming this bridge between masculinity and femininity for the modern man/ modern couple, who are ready to share everything from daily chores to fashion and beauty.

4) How do you think masculinity, hair, and self- identification intersect?

I think hair, whether its on your body or in the form or a moustache or beard, is still a symbol of manliness and masculinity. I still remember when Tiger Shroff made his acting debut in 2014, he was trolled for being ‘girly’ as he had smooth skin and no facial hair or moustache – which was not ‘manly’. His physical strength was totally ignored, and more attention was paid to his face.

So, it definitely raises questions about what parameters you take into account when expressing your identity, and where society’s expectation come into the picture.

5) Are there any specific interactions with the barbers that you remember in particular?

There were many stories that struck a chord. Nawab, the Belleza Gents Beauty saloon owner, for instance, learnt everything about being a barber on his own, as nobody in his family is of this profession. He’s been working since 2002 and has owned his own salon for a year now.

Then there’s the Bombay Saloon shop owner Nawaz who gleefully remembered the exact date his shop opened: 1st April 1997. For the past 20 years, he has been working in the shop alone, as his son works aboard a ship. His brothers also work as barbers, and own their own shops.

Shamsudheen’s shop is one of the oldest in Kochangadi. It has been around for about 75 years. He is oblivious to new trends and fashions in the hair cutting business that caters to the youth, he remains loyal to his customers and vice versa.

6) How many new hairstyles did you come to know about through the project?

Love this question. I learned not only the local and international names of the cuts but how to differentiate between two cuts with little variation. I also learnt how one hairstyle is known by different names in different regions or states. For instance, what you call a ‘Mushroom Cut” in English, is called a ‘Cap Cut’ in Kochi and ‘Katora Cut’ in North India.

For more information on Pallavi’s project and residency, click here.

Written by Aishwarya Menon

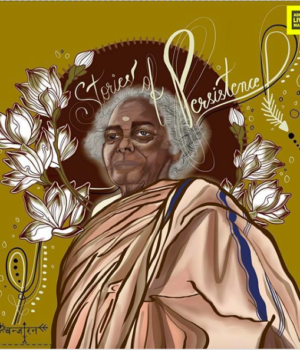

All images credit: Kochi Muziris Biennale