Photographer Abdul-Halik Azeez knows how to take a good picture.

Born in Colombo, Halik was a former strategy consultant and journalist for the Sunday Leader. His interest in journalistic and conceptual photography led to him documenting his observations on Instagram. Today, Halik aka Colombedouin has more than 25,000 followers on the platform. His practice has expanded to include a lot of conceptual photography and the use of other spaces and mediums such as gallery spaces and zines.

In tone and subject matter, Halik’s photographs range from quirky to shatteringly tragic. Some are glimpses of everyday Sri Lanka as the country grapples with history and identity through a decolonial lens; some encapsulate a fraction of a moment in a person’s life; and others chronicle Halik’s own frames of mind as he investigates modern identity, self-narrative, and memory.

We chatted with the photographer about his ideas and images:

Why do you take photographs?

I suppose I started taking photos as some sort of reflexive action to deal with my immediate environment. It was a way of coping with the new, a way of convincing myself that here I was, absorbing, categorising, learning, remembering. It was a way of taking control of and possessing my environment. I have since read too much and thought about it too much to believe this, the false promise of photographs, in such a reductive manner any longer. This dogma about photography is partly what gives it its usefulness as an imperialist, colonial and cultural tool of domination.

An image is a fleeting moment that I would now be very careful before associating with ‘memory’ or ‘record’ any longer. Perhaps because, now, through practice, I have a an idea of the subjective processes that go into making an image. Also, I think we’re living in a post-memory age, all we have are images now. Which means we need to re-evaluate what photography is today.

Imagery is the medium through which the history of our present is being written. But then the actual nature of what we call memory itself is interesting to examine, but maybe not here!

I use photography now as a medium to record visual incongruences, moments in which the semiotics of the world around me conspire to create something like beautiful poetry.

Visceral moments that stab our comfortable inherited cultural representations like a knife. At least, those are the kind of things I like to try and capture now. I use it to deal with my own cracks in perception, confusion, overlapping ideologies. I think vision is a beautiful thing, and reality honestly is something that morphs in relation to the perceiver.

If you look close enough, and in the right places, you can always find things to see that will speak to your inner urges. Give you the answers which you seek.

I think photography is also a really accessible medium. Anyone can do it. Most of my photographs are taken by my phone. Besides the cost, an expensive camera, even if it is a small one, immediately presents itself as a camera. A phone on the other hand, is a camera and isn’t a camera at the same time. This duality gives it just enough of a disguise to make it the ultimate stealth camera because it can often hide in plain sight.

And what are some key elements of your photography, whether conceptually or aesthetically?

One of the primary elements is candidness, most of my photos are taken in fleeting moments and often without even looking at the screen. I take a lot of photos, and have thousands of them which I can’t keep track of.

I am very interested in ’urban iconography’, by which I mean the semiotic landscape of cities. Everything around us can also be viewed as a symbol whose shape or form embodies histories, ideologies, cultures and meaning.

I like to capture how these various meanings interact in our ‘natural’ habitat. Meanings can morph, change, become the exact opposite of what they started out as.

Lately, my face has been an element in my work. It’s a late entry into selfie culture, and maybe a reflection on it. I have been trying to capture the defragmentation of the self that we experience, when it is more obvious than ever today that our identities are constructed through institutions, cultural memes, late-capitalist categories.

This series captures my readings into Lacan and other post-modernists, as well as my understanding of notions of the self coming from the cultural, spiritual and religious traditions I am familiar with.

Aside from that I have also done work on issues of urbanisation in Colombo and on Sri Lanka’s post-war ethno-nationalist conflict. There is an element of photojournalism to my work that comes from my background as a journalist. And of course I am really keen on writing as a part of my output. Text is also an interesting subject to photograph.

You grew up in Sri Lanka. How has that influenced or affected your work?

Sri Lanka’s historical, geographic and cultural positionally in many ways is also mine. Decolonial thinking would not have become a central part of how I see the world, for better or worse, if it wasn’t from coming from a colonised culture. Of course it was also informed by me being able to access decolonial literature, thought and teachers which I wouldn’t say is something that simply crosses the path of the colonised without significant effort being made.

One thing that frustrates me about being in Sri Lanka is the widespread buying into of neoliberal ideology. This is what is driving its post-war economic aspirations, but under the hood, a lot of cultural damage and carnage is going unchecked because what we’re losing is considered to be valueless. There is very little reflection as to how our post-independence environment and its colonial hangovers, and developmental fetishisms have driven the conflict and carnage that has ripped this country apart.

Tell us a bit about your ‘Sub Urban Poetry’ series. And ‘The Violence of Memory’

Sub Urban Poetry was a series I realised I had only after retrospectively looking at some of my pictures, and discovered I had a new, emerging theme more explicitly focussed on iconography. It was interesting to me to note how some of these micro perspectives which I had captured spoke very clearly on the macro transformations happening in Colombo.

What happens when the intended meaning of the sign merges with the perceived meaning of the observer, diluted and added to by being just one component in an entire semiotic field? Moreover, what happens when this convergence is then made into an image and displayed as art? How does that then inform the meaning of this sign, now a composite image, itself interacting with the perspective of yet another viewer, diluted and added to within a gallery space? These were some interesting ideas I got to experiment with with this series.

Violence of Memory was a photojournalistic and conceptual series which involved a fair bit of research for the narratives, and then involved a fair bit of planning and execution for the pictures. It is not how I normally work. I normally adopt an approach of minimal planning, preferring to ‘go with the flow’ with a basic structure and idea, and then see what happens. For this reason it was a refreshing project to do.

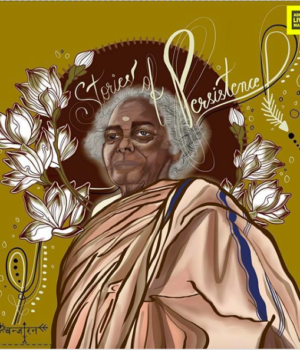

I got this commission in late 2014 when Sri Lanka had just seen a shocking wave of attacks against minorities. Coming so soon after this war, this was a huge blow to everyone who had dared to begin imagining a future free of conflict for the country. As a member of a minority community, journalist and activist I had been trying within my own capacity to respond to these events. This series was one of those responses.

What do you want your viewers to take away from your work?

I like to think of my work as activist in nature. What I would really like to do to people who see my work is to create some sort of cognitive dissonance, a moment of reflection that might somehow sit and fester and over time, to trigger something that would raise a question or two into irresistible investigation from somewhere in the murk of the imagination.

But it is also fascinating to know that somehow, no matter what I try, my work can only probably elicit the kind of reaction I want entirely by random. If the author is dead, then the work is entirely at the mercy of the audience, which is why I am interested in thinking of the artist/communicator as a medium alone. A medium that transmits a message doing no more than what would occur to it if it were transmitted through another medium such as radio for example. The medium in both cases, albeit to different degrees and ends, moulds the message, adds an agenda, and then propagates it over a given space and time.

Since storytelling and narrative are the heart of what you do, in your opinion, what defines a successful visual narrative?

I think it’s kind of like what judge Potter Stewart said when asked to define pornography, “I know it when I see it”. Or in this case, “I know it when I feel it”.

I think for me a good visual narrative is something capable of transporting you entirely into its world, even if only for a brief moment. It absorbs you long enough to leave an impact that you walk away with.

What’s the most important thing that photography has taught you?

Working with it as a way of producing art has taught me to trust my instincts more, and as a medium it has challenged me to learn to look at things in new ways, especially when it comes to responding to challenging project ideas. Also, having taken most of my shots on my phone, I think I’ve learned that the best camera is the one you always have with you.

You can find more of Halik’s work here, and follow him on Instagram by clicking here.

Interview by Pavi Sagar

All images credit: Abdul-Halik Azeez